THE PLAYHOUSES OF OUR GRANDPARENTS, Actes Sud EDITION, 2011

PREFACE

The playhouse sets the stage, all around the world.

Growing up, our “playhouses” were our imaginary hideaways, sanctuaries where we felt protected, surrounded by our favorite things. Our own little theater set where sheets metamorphosed into oceans, and piles of books became islands inhabited by Indians, Pygmies or Robinson Crusoe. Whether created in the backyard or under the covers in our bedroom, when we designed and built a children’s fort, den, or playhouse, we invented a whole new world in which to play, dream and let our imaginations run free. When I was little my Grandfather taught me the art of woodworking and my grandmother that of sewing. Later as an adult, quite naturally I turned back to my grandparents when I wished to relive some of those magical moments we had shared, when gestures spoke louder than words; and it was there and then that I took my very first photographs of my own grandparents. From these first images, the project «Playhouses of Our Grandparents» was born : my personal quest to seek out and meet our elders and give them a voice. I wanted to explore with grandparents all over the world the games and pastimes of yesteryear, rich channels of transmission, wisdom and knowledge. So I set out to discover the world, with nothing more than my camera, a bag of rope, clothespins and some studio spotlights.

With every new encounter I would show people those first photographs of my grandparents’ playhouses – photographs I had glued in a sketchbook, or other shots taken in towns, villages or countries where I’d just been. This photo-journal explained my ideas better than any verbal description ever could have. Along the way, I realised how the Playhouse is a universal concept. Inside every one of us, lies the youthful spirit of a child who revels in creating with everyday items around him, a world invented entirely by his imagination.

When arriving in a village, I would search out my “accomplice.” Often this was someone around my age who was inspired to convince his own grandparents to join in the adventure of making a Playhouse. Explaining the concept of building a children’s fort was always a good way to get creative juices owing. Based on the concept that for me, any grandparent was perfect for the part, my accomplice would often start by presenting me a member of his own family, a neighbour or key community figure. Given the magic of word-of-mouth and human curiosity, the invitation to participate in playhouse-building spread like wild re and gradually more and more people came forth to participate. This enthusiastic support meant we could build and photograph a new playhouse every day.

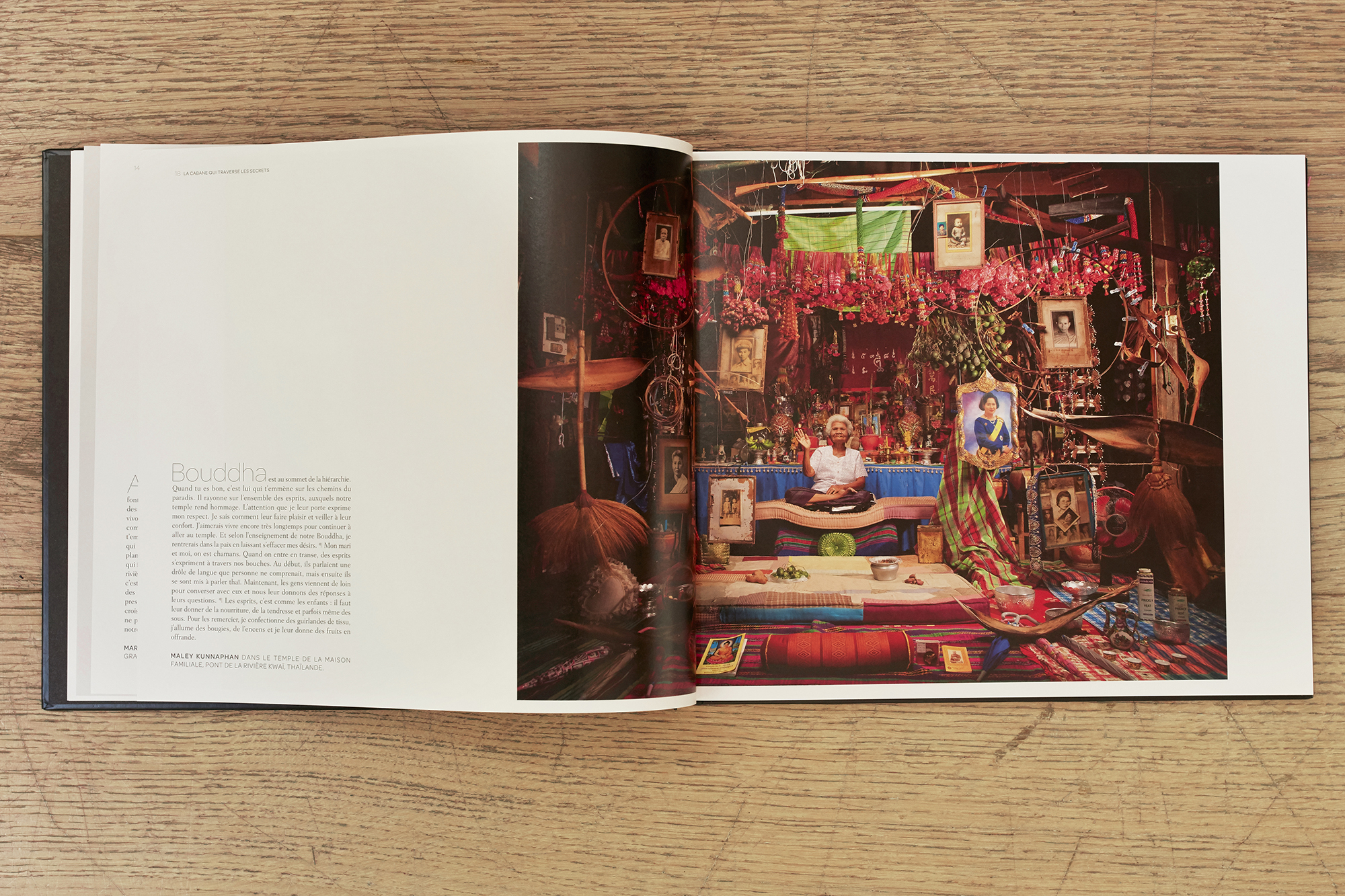

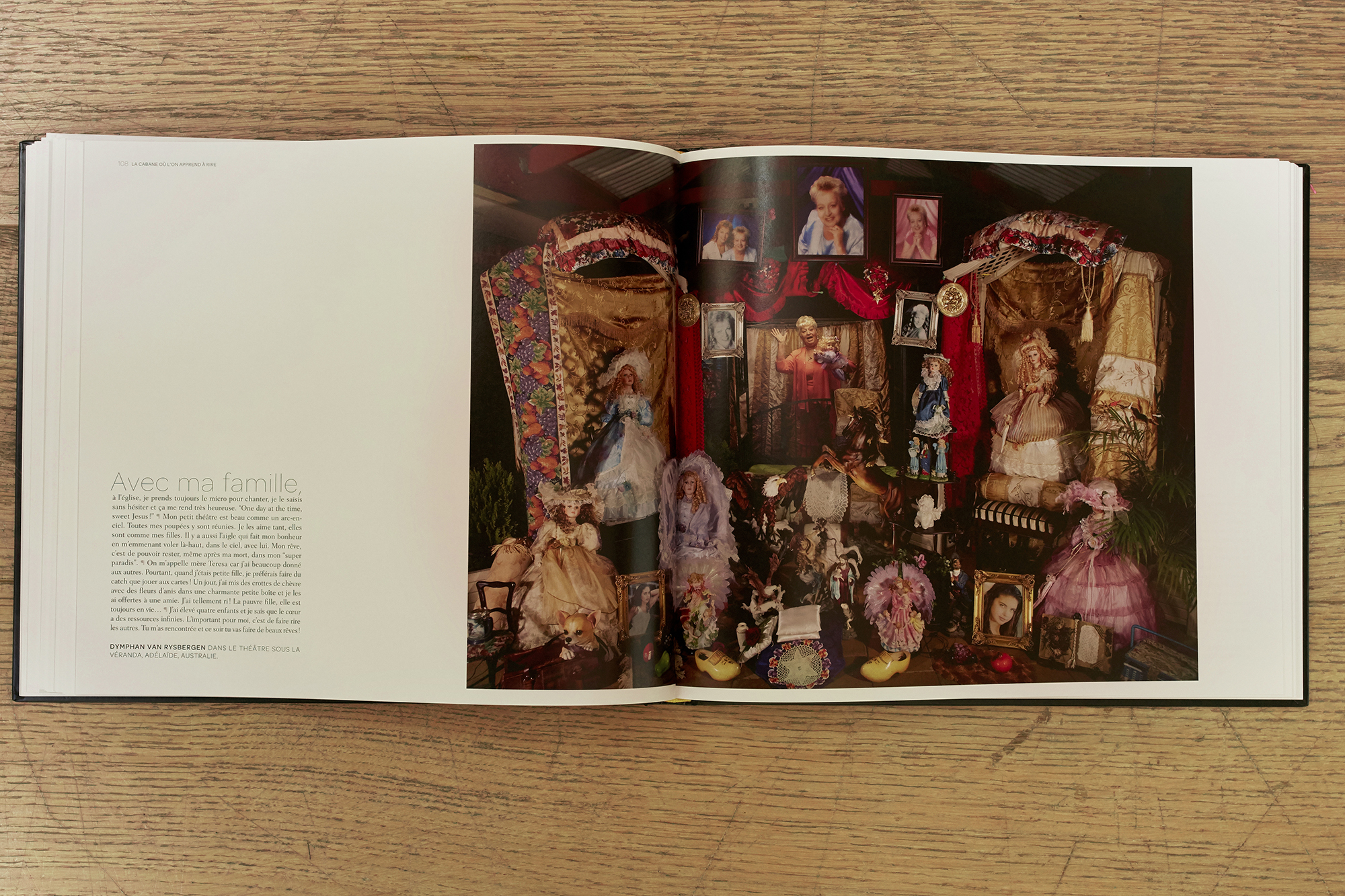

Over time, my installations became bigger and more elaborate, built primarily outdoors, often on symbolic sites, so that what might start as a simple photo-shoot would often turn into a full- edged theater set. Playhouses were built from the stuff of elders’ lives, objects from their past and present, the very foundations of their existence. Utensils, knick-knacks and all kinds of tools were then arranged and staged, juxtaposed according to individual ideas and the tales the grandparents would tell during the course of installation. The Playhouse gradually became a vehicle for freedom of speech, a setting where memories, revelations and the joy of sharing reigned.

Sometimes, up to forty people would collaborate, with more than a hundred spectators gathering around to watch the work in progress. This theatrical setting and captive audience often set the stage for spontaneous oratory outbursts from members of the community. From a single playhouse, countless words sprung forth.

Three key elements are essential in contributing to the success of this kind of spontaneous show.

First, we must have a story to tell, as, when we do, the world welcomes us with open arms. While sharing the pages of my photo-journal, sometimes I’d end up telling the story of my grandparents a good dozen

times a day. I’d enthusiastically abandon my book to villagers curiosity; accepting that it would suffer in the hands of children’s unbridled enthusiasm, and as the journal was passed around, stoking more and more interest, so would grow the gossip, rumours and “buzz” about the mysterious makeshift theater taking shape in the village. As time passed, I became more comfortable in my role as spontaneous merry- maker and as the doors of individual’s imaginations opened wider, so did those of the village - offering food and shelter, but also, at the same time, a certain sense of responsibility to guarantee the success of the show.

Secondly, imagination is needed in order to compensate for the modesty of the tools at one’s disposition during the building process. In more urban settings, Playhouse building often resembled that kind of “living out of a box” atmosphere that one encounters when moving, inspiration fueled by digging into boxes of “stuff” and while pouring through old family photo albums. While in the countryside, a pair of scissors could be transformed into a machete, gaskets grouped to resemble creeping vines and tangled bark made to look like the rope of a swing. To create solid arbors and arches, I’d split bamboo in quarters and once we had a solid frame we were able to pin large leaves in place using thorns. In the glare of the sunlight or that of my spotlights, these large vegetal screens would produce a greenish stained-glass- window effect.

I’d dig with my bare hands to unearth the stones to use as wedges to hold stakes in place. When the ground was too hard, heavy counterweights were hung from the feet of the structures, while stays were attached at the pinnacle. When there were no tree trunks around to use for support, I’d bind up clumps of grass and affix the ropes to them. There is always strength in solidarity and when it came to hanging things, often the lightest member of the tribe or community was sent scurrying up a tree with safety ropes around his waist in order to attach sheets or other elements.

During the building process, each of these movements evokes a spirit of authenticity, that of simple and honest individuals, like the sailor hoisting his sails or practicing the art of knot-tying, the farmer devising cunning ploys to keep his beasts in check, and even kids with the creative things they build. In the end, we’re imitating the movements of those billions of skilled anonymous labourers who make up half of the population today, those men who naively and majestically live in harmony with Nature and build impressive architectural structures with only their bare hands.

The third element is that of spoken word. As the result of long hours of respectful listening, my playhouse journal is full of hundreds of pages of strange and mysterious anecdotes. As my subjects recount their stories, in the process of taking copious notes, I too become a storyteller. Interviews with grandparents took place in the context of each playhouse; their messages are hidden in the foundation of the designs, and are the wind behind my creative direction. When the rhythm of construction and telling of stories were in sync, and providing that the installation didn’t collapse for any unforeseen reason, the recounting of the grandparent’s stories could become colourful speeches addressed to a sometimes rather large and rowdy audience. The support of an attentive crowd helped nourish the exuberance of oration. My playhouse photographs are not classic studio shots featuring rigid figures staring vaguely out to sea, nor stances of unaffected poseurs wearing artificial attitudes. The joy expressed on my subject’s faces is that of a loving gaze one bestows on someone they care about.

Often at the end of a shoot, after we’d managed to clean everything up and put away all our “toys”, we’d gather together for an end of evening chat, a lively debriefing where everyone dug deep into their memories and reflections, contributing eagerly in the hopes of adding their own words to that of the elders and thus their own personal touch to the pages of my journal.

The Playhouse project took me to forty countries where I produced over four hundred portraits. The innate map-reading skills of my friend Thomas often set my morning compass straight on those days when I was unable to recall which part of the world we had landed in. His sense of direction and ability to

tame the most uncooperative vehicles saved us from many scrapes, like guiding us through masses of thick fog and navigating a sea of Tata trucks hurtling down Nepalese or Andes mountain slopes, so close you could feel their door handles brushing against yours. The further you go from big cities, the smaller airplanes become and you have to run to be the first to ll the hold. We spent long evenings working out the best strategies to ensure how our three hundred and thirty pounds of lighting equipment would travel on with us to new destinations. We’d strap our spotlights and batteries to beasts of burden, on the narrow bridges of riverboats or onto rooftops of buses.

For long months I paid constant attention to the moods of the sky: from the way the wind influences the movement of the clouds to the process of how formations take shape and dissolve as influenced by altitude and reflections from the sea, acting as a giant mirror. The position of the sun provided an essential indicator for arranging the playhouse set and adjusting the orientation of the camera. Through Thomas’s diligence and expertise in lighting we managed to make the most of both artificial and natural lights. We were able to capture moments of grace, ephemeral and symbolic. Like that moment at day’s end, when colour is majestically splashed across the sky somehow mirroring the joyous contentment felt by these grandparents in the twilight of their lives.

The world into which our grandparents were born was one where people often lived and died all together under the same roof or canvas tent. Today the transmission of language, history and traditions, as well as our knowledge of nature and biodiversity, is highly influenced by media and education systems. The verbiage of the television holds more value than the wise words coming from our grandmothers. The disillusionment felt by many urban dwellers comes from the fact that they are daily spectators of a success they will never share. They feed off nostalgic memories of a time when man did not live alone in the middle of the crowd. Today, global models have replaced family traditions that were once passed down. In rural settings, we are now producing generations unsuitable for a community way of life, incapable of deriving survival solutions from nature. The figure of an elder no longer commands the respect it once did. Once upon a time, grandparents were synonymous with authority and wisdom; today they are often seen as weak and lonely. During the playhouse adventures we laughed and cried every day and I realised over time, that joy and creation are the best weapons we have to fight the tragedy of the human condition. Transformed into kings and queens for a day, the grandparents I met around the world taught me to have faith in the extraordinary ability of human beings to open up to one another. Living with genuine willingness and a brave heart to welcome the unknown can help us transform our perspective about the world and our fellow human beings. To do this, just build a Playhouse with a few yards of rope and some pieces of wood, and then declare it your palace. From beneath this taffeta, raffia and batik, the words of our elders ring out, and thus the story begins ...

Nicolas Henry